Harry Potter and the Perfidious Persian Publisher

Harry Potter and the Perfidious Persian Publisher

I wrote recently about how Januskevic, the Belarusian publisher, had a difficult time renegotiating their publishing rights with The Blair Partnership due to UK sanctions against Belarus. That got me to thinking about the publisher of the authorized Persian / Farsi translation, Tandis. There have been UK sanctions against Iran on and off since their first edition of Philosopher’s Stone was published in 2000.

We do know that Tandis was originally granted the rights to publish their translation because it appeared on J.K. Rowling’s original “contacts list” which listed the authorized publishers. Notably, Farsi was not on The Blair Partnership List that surfaced in 2016; however we cannot really draw any firm conclusions from that fact, as there are publishers that were on the “contacts list” that were not on The Blair Partnership List and subsequently published further authorized editions (Afrikaans for example). It is pretty clear that the 2016 list was a list of active rights contracts and nothing prevented inactive contracts from being renewed or renegotiated.

Generally I have been inclined to accept that, without evidence to the contrary, a publisher that had legally obtained the rights to publish Harry Potter remained in compliance if they continued publishing. For the most part, I think that is likely a safe assumption; particularly in countries that have strong legal protections for intellectual property.

That isn’t Iran—obviously, it’s a free-for-all there as far as IP. Even if Tandis had every intention of only publishing Harry Potter legally, how would they react if they were denied, not out of their willingness to comply, but due to sanctions against the country?

I did try to find out whether sanctions would have directly impacted Tandis’s ability to do business with TBP and it’s not clear, especially to me as non-expert on international IP law and sanctions. However, it seems unlikely that Tandis would be specifically targeted, nor books in general—restrictions are all quite specific to named entities and those generally aren’t private companies. Where the impact would most likely be felt is in the restriction of financial transactions. We’ve seen this ourselves—it’s possible to find places to buy the books and even ones that would be willing to ship outside of Iran, but there is no way to pay.

There was a period between 2011 and 2015 in which the UK forbid any financial transactions with Iranian banks, and they are currently forbidden now, since 2023, due to Iran’s support of Russian in its war with the Ukraine. It would be exceedingly difficult for Tandis to pay TBP anything it owed them, although not impossible.

Apparently, even under strict regimes, the UK often has exemptions for IP transactions which would allow those transactions to take place. But it is still conceivable that Tandis and TBP could come up with some agreement for Tandis to just hold onto anything they owed to be transferred when sanctions were lifted (it’s not like TBP or J.K. are desperate for Iranian royalties!) or, if their contract was genuinely nullified, to pay back-royalties upon renegotiation later.

That’s all speculation—I’m just throwing out scenarios in which I could imagine Tandis remaining in TBP’s good graces.

I can equally imagine that if Tandis was unable to renew their contract, they would not be that fussed. Clearly TBP has no ability to enforce copyright within Iran, so why would Tandis give up a bestselling series?

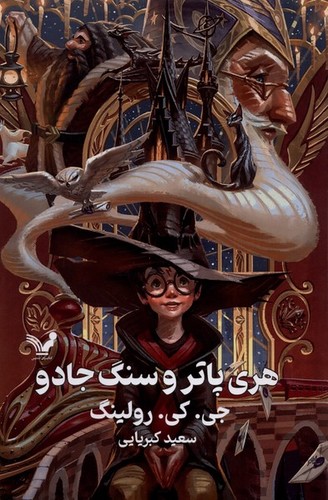

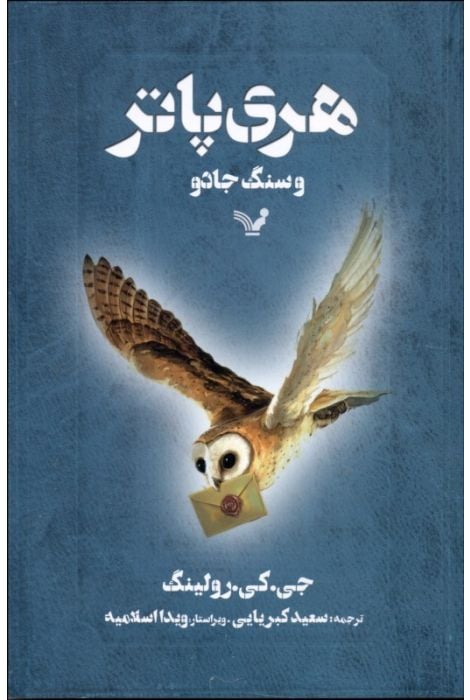

Most recently, Tandis has published a hardcover series with Apolar art and a paperback series with all new AI-generated artwork. (Philosopher’s Stone of each series depicted below.) Based solely on the books themselves, I don’t think it would be possible to conclude whether they are authorized or not.

| Title: | هری پاتر و سنگ جادو |

| Transliteration: | Harī Pātar va Sang-e Jadū |

| Translator: | |

| ISBN: | 978-600-182-828-7 |

| Published: | 2022 |

| Publisher: | |

| Links: |

| Title: | هری پاتر و سنگ جادو |

| Transliteration: | Harī Pātar va Sang-e Jadū |

| Translator: | |

| ISBN: | 978-600-182-828-7 |

| Published: | 2023 |

| Publisher: | |

| Links: |

If I were to judge the AI-cover series out of context purely on their own, I would absolutely conclude that they were unauthorized books. They have none of the standard, required text on their copyright pages, no Wizarding World logos, and I highly doubt that the TBP would ever approve AI-generated artwork. However, all of that is equally true of Tandis’s first and confirmed authorized edition that was published for more than a decade—we have no idea why that was tolerated before; we can’t conclusively say that it’s not being tolerated now.

Fortunately, we don’t need to speculate: in a rare communication, TBP confirmed via email that Tandis does not currently have an agreement for the publication of Harry Potter—specifically in reference to the AI-covers.

Tandis is no longer an authorized publisher of Harry Potter.

This raises two important questions: one practical and one philosophical. Practically as collectors, it would be nice to know when Tandis stopped being an authorized publisher—sadly TBP declined to provide that detail. It is very likely that the Apolar covers are not authorized; it’s less clear whether the below edition of PS and it’s siblings may be unauthorized too:

| Title: | هری پاتر و سنگ جادو |

| Transliteration: | Harī Pātar va Sang-e Jadū |

| Translator: | |

| ISBN: | 978-964-5757-02-9 |

| Published: | 2014 |

| Publisher: | |

| Links: |

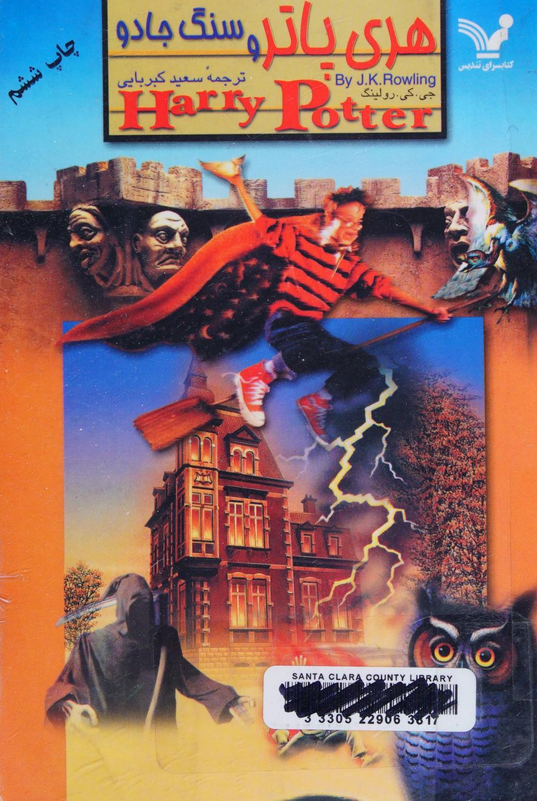

For that matter, it is entirely possible that later prints of the original edition (below) are also unauthorized:

| Title: | هری پاتر و سنگ جادو |

| Transliteration: | Harī Pātar va Sang-e Jadū |

| Translator: | |

| ISBN: | 978-964-5757-02-9 |

| Published: | 2000 |

| Publisher: | |

| Links: |

It was published until at least 2013 after which is was replaced by the edition above in 2014.

I have a 2008 article in which the main Persian translator, Vida Eslamieh, rails against piracy—I would take that as weak evidence that Tandis was in compliance then. And we know that they did not have an active contract in 2016. If I was to hazard a guess based on these very scant facts, I would say that most likely Tandis’s lost their publishing rights around 2011 when the UK financial sanctions were leveled against Iran. That is also around when Blair took over and we know that they have been much more strict about conforming to requirements, approving covers etc.

That makes any of the books published after 2011 illegal…

Regardless, we know that the AI-covers are illegit and this is the first time that we have seen this situation arise: a publisher that had obtained the rights to publish a Harry Potter translation, loses the rights and continues to publish the translation anyway. Philosophically, what are the consequences of this fact? What do we call these books?

We have seen unauthorized translations become authorized (Nepali, Russian and Bengali)—can an authorized translation become unauthorized? I would argue “no”; that once authorized, always authorized. Consider Greenlandic: it has been out of print for a very long time. The original publisher is defunct, the translator has passed—that text is about as far out of having a current rights-holder as it is possible to be and yet we still include it in the list of authorized translations. When we speak of “authorized translations” we implicitly understand that as a static property—that at some time during the publishing history of Harry Potter, the publisher of that translation was legally entitled to publish that book.

Clearly, although it is an authorized translation, the physical books that have been published recently, were not published legally. We do have already have a category for illegal copies of a legal book: “bootleg”. I realize at first this seems like an unintuitive term of apply to this case. Usually we think of bootlegs as copies made by a third party, usually concurrently to the authorized books. However, I think it applies. Consider Greenlandic again for a moment: if a new publisher started reprinting the original translation again right now without having first obtained the rights, we would be comfortable calling it a bootleg. Obviously, “concurrence” isn’t necessary.

Suppose that Atuakkiorfik-Greenland Publishers, had their books printed by the ACME printing company in Denmark. Suppose that the ACME printing company retained a copy of Harry Potter ujarullu inuunartoq and decided today that it would be great to print another 100 copies without getting permission from Blair. I would still call those 100 books “bootlegs” even though the original and the new books were physically produced by the same company. Is it a stretch to then, to say that even if it’s the same publisher, “bootleg” still applies?

Where our intuitions are likely to start to create some cognitive dissonance, I think, is if you were holding the last (hypothetical) legal print and the first (hypothetical) illegal print of the first edition. The text is the same; physically they’re identical. Printed by the same printers with the same files using the same machines—indistinguishable except by the print number. In reality, to what degree would the psycho-social label of “bootleg” genuinely impact how we think of the two books? And how much would it impact the general public?

So impressive! 👍

I am genuinely impressed by such a comprehensive investigation. There are very considerable points from several angles that make me think of what happened to the publisher and why they are at this point. It

There should be a good story behind the scenes, and it might be worthy of being heard.

I’m just interested in learning more about it.