Harry Potter and the Myanmar Market (Part 2)

Harry Potter and the Myanmar Market (Part 2)

When I was introduced to the unauthorized Myanmar translations of the Harry Potter series by @knockturnerik and @mcallister_alaskagrown in the summer of 2019, I had no idea it would turn into the most difficult and complicated investigation I have undertaken. Sorting out the history of Harry Potter in this relatively small Asian country has been confusing, aggravating, surprising and delightful. What follows is, I believe, the most comprehensive compilation of these editions that exists. Indeed, possibly the only time it’s been attempted. The complete catalogue of identified translations follows the article proper below.

Acknowledgements

First I have to acknowledge the contributions of two people that made this investigation possible.

@mcallister_alaskagrown acquired as many of the books as he could find (including my copies of three of the Philosopher’s Stone translations) and supplied me with so many photos including many of the cover photos you will see below. Not a lot of people share my passion for the unauthorized translations and he is definitely a kindred spirit.

Lucas Stewart, a UK-born author and blogger living in Myanmar, was kind enough to answer a lot of questions about how things work in the country and without him I’d still be staring at photos, too confused to move forward.

I would also like to thank my dear friend ELT for providing valuable feedback on my drafts.

Myanmar vs. Burma/Burmese

If you’ve asked yourself, “Should I say ‘Myanmar’ or ‘Burmese'” you’re not alone. As you will see, like everything about this country and language it’s complicated. But long story short: it doesn’t much matter. For all intents and purposes, they are interchangeable. For my part, I will defer is ISO-639-3 which defines language names and language codes: they use Myanmar (MYA) and so I will too.

The Technical Challenges

The Myanmar writing system: This investigation was my introduction to Myanmar; I would have recognized it before, certainly, but I had never tried to work with it. Structurally it is similar to other Indic scripts like Devanagari—scripts I am comfortable with—so it didn’t intimidate me. That said, I have to admit it kicked my ass.

၁ ပ င ဂ ဎ ဝ ၀

Those are different Myanmar letters—yes, even the last two which are Unicode x101D and x1040 respectively. It doesn’t get better from there—there is so little variation to hang meaning on it just slides right off my brain onto the floor. I’m starting to be able to recognize whole words when I know where to look, but spaces are not obligatory in Myanmar and generally not used to separate words but rather clauses, so even trying to parse out words is challenging. I have no idea how to pronounce any of it.

Myanmar romanization: The official romanization of Myanmar is the MLC Transcription System. Google Translate uses it and it is, for many technical reasons, superior to other systems. Unfortunately no one else actually uses it. Worse, competing romanizations appear to have only a passing similarity to each other. For example, one of the Harry Potter translators is မင်းခိုက်စိုးစန်. The common transliteration of his name is ‘Min Khite Soe San”. In MLCTS it is rendered: ‘Mainnhkitehcoehcaan’. This pair are reasonably similar—there are much worse divergences. You can see why people prefer the former and ultimately, the romanizations help very little in trying get a handle on working with the language.

Myanmar text encoding: Before Unicode, writing text in other languages was extremely difficult. Computers used 128 characters / code-points and that was all you got. To use a different character set, you would have to specify I different “code-page” and specify the right font to display it. Early attempts to get non-latin text often started by simply using a different font to make Latin characters look different. Because of the complexity of the script and the fact Myanmar was subject to international sanctions during a time when Microsoft and Apple were helping countries modernize, Myanmar is still in a state of transition.

128 character encodings still pop up, but really only in PDFs, where the fonts are embedded so that you don’t see the gibberish—unfortunately, that also means they are effectively unsearchable. The biggest problem online is Zawgyi, a home-grown Myanmar Unicode font that isn’t Unicode compliant. To be fair, The Unicode Consortium wasn’t even done fiddling with Myanmar encoding until 2008, so Myanmar speakers can be forgiven for trying to just get something usable out there. Although any modern operating system handles Unicode Myanmar beautifully without any difficulty, the transition has been slow and is incomplete. The Myanmar government decreed “U-Day”—the day the entire country would flip the switch from Zawgyi to Unicode—on 2019-10-01; only just over a year ago! Even then transition is expected to take a couple of years.

Google, thank the internet ghods, takes Zawgyi into account and treats them just the same in search. Of course when you click through, you get text that looks like this:

ဟယ္ရီေပၚတာႏွင့္ေမွာ္ေက်ာက္တုံး

Instead of this:

ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်မှော်ကျောက်တုံး

In which case, you copy and paste it into a Zawgyi<>Unicode converter to make it something legible.

Google takes the difference into account—but no one else does. So if you’re trying to search an online book store or catalogue, you need to figure out which encoding they use and then convert your search terms appropriately. Same for searching on a page. Oy vey.

Myanmar came late to the party: Widespread internet use is relatively recent in Myanmar. The first Harry Potter translations started coming out it 2002—personal computers were only capable of rendering complex scripts in 2004 and Myanmar fonts using those capabilities became available in 2005 and, as I mentioned, were still being modified until 2008. There simply is no internet history from that time in Myanmar which makes research really difficult. Even now, (subjectively, it seems that) half of Myanmar’s internet activity is on Facebook1. Facebook is the entire web-presence for many, if not most, publishers (and Facebook users do seem to love their Zawgyi!).

Google Translate: In Myanmar, it is simply terrible. Indispensable and forgivable (some of those Zawgyi Unicode non-compliance issues really impede the work of natural language processing and Myanmar content is both relatively new and sparse), but just truly awful. Translations are very sensitive to whitespace like spaces and newlines (ironic since, as I mentioned, spaces are optional in Myanmar text!). For example, the only different between these two bits of Myanmar phrases is a single space:

| Myanmar | Google Translate |

| ပြည်ပအားကိုးပုဆိန်ရို၊အဆိုးမြင်ဝါဒီများအား ဆန့်ကျင်ကြ | Opposition to external forces and pacifists |

| ပြည်ပအားကိုးပုဆိန်ရို၊ အဆိုးမြင်ဝါဒီများအား ဆန့်ကျင်ကြ | External support Oppose the Negroes |

Names are completely messed up: the aforementioned Min Khite Soe San is translated by Google Translate as “Assault”. Usually, if Google can’t translate something, it will throw in a placeholder—in Myanmar, it likes to just leave it out. The translations do at least give you some inkling of what you’re looking at but there is a lot of head-scratching and experimentation while trying to tease out anything sensible.

Update: The article hasn’t even been published and I’m updating it! Google translate is a rapidly moving target in Myanmar. Even in the last couple of months the translations it provides for the same text is radically different. Largely it is an improvement and it is handling personal names much better. But it’s not universally better; for example the same two bits of text above are now translated as:

| Myanmar | Google Translate |

| ပြည်ပအားကိုးပုဆိန်ရို၊အဆိုးမြင်ဝါဒီများအား ဆန့်ကျင်ကြ | Oppose foreign ax-wielding pessimists |

| ပြည်ပအားကိုးပုဆိန်ရို၊ အဆိုးမြင်ဝါဒီများအား ဆန့်ကျင်ကြ | The ax of foreign power; Oppose the pessimists |

I guess at least it’s less racist.

Google redeems itself and saves the day: As bad as Google Translate is in Myanmar, Googles Myanmar OCR is incredible. I was utterly blown away and I would not have been able to do this investigation without it. And who knew it even existed? Myanmar is not included in its other projects like its AR translation service in the Google Translate app (where you can use your phone camera translate in realtime). I found an obscure reference and instructions in a random PDF online: upload an image of the Myanmar text to Google Drive. Right-click and “Open in Google Docs”. It did not matter if the text was grainy, white on grey, on an angle, warped, in a Gothic Myanmar font… it was perfect. Formatting left a little to be desired and the text always shows up inexplicably in some shade of yellow/gold/brown but these are not things I care about. So thank you Google! We do not see eye-to-eye on many things these days, but I have to hand it to you, your Myanmar OCR is superb!

What Makes the Myanmar Market Unique

Aside from the technical challenges, publishing in Myanmar is not like it is elsewhere in the world. Here, I owe a debt of gratitude to Lucas Stewart—he provided a the necessary context to understand many of the mystifying things I was observing. Things like:

- books that have a different publisher on the cover than in the print matter

- pen-names

- names that include text in parentheses

- weird pages of text in the front matter

A lot comes down to the fact that between 1962 and 2011, Myanmar was a military dictatorship. International pressure led the military to agree to reform and a new constitution was adopted in 2008 leading to elections in 2010 and the ceding of military power in 2011. The situation remains complicated and Myanmar is still considered an authoritarian regime, but a lot of the previous restrictions on the publishing industry have eased up. Since 2012, the military no longer censors manuscripts and the international sanctions that made paper, ink and printing-press parts in short supply and extremely expensive have been lifted.

Modern international publishing standards—ISBN numbers, copyright—are still somewhat alien concepts, however. The industry is gradually improving, but change moves slowly. In the meantime, it means that unauthorized publications are flourishing and you can take nothing for granted.

Publishers: Authoritarian governments are, as a rule, extremely concerned about the information their citizens have access to. In Myanmar, before the reforms, the military controlled the paper supply. Publishers needed to be licensed and registered, books and their covers needed to be approved and permitted separately through a censorship board, and “mandated clauses” (more about these shortly) needed to be printed as part of the front matter. The exact requirements were a bit of a moving target—bureaucracy as a form of control. Oddly enough though, unlicensed publishers—sometimes just an author publishing their own books—were allowed to “rent” the registration number of a licensed publisher.

To give you a sense of how confusing it can be, I’ve included the internal publisher information printed on the inside of two of the first Philosopher’s Stone translations, below—the 2002 translations by Kyi Kyi Mar and Min Khite Soe San:

| ထုတ်ဝေသူ | – ဒေါ်မိုးကေခိုင် (၁၁၆၉၂) – ချိုတေးသံစာပေတိုက် |

| htotewaysuu | – dawmoe kayhkine ( 1 1 6 9 2) – hkyao tayysan hcarpaytite |

| Publisher | – Daw Moe Kay Khine (11692) – Sweet Music Library |

| ထုတ်ဝေသူ | ဒေါ်မိုးကေခိုင် (ချိုတေးသံစာပေ) (၀၁၆၉၂) |

| htotewaysuu | dawmoe kayhkine ( hkyao tayysan hcarpay) ( 0 1 6 9 2) |

| Publisher | Daw Moe Kay Khine (Sweet Music Literature) (01692) |

I specify “internal” because, the publishers on the cover don’t match the inside at all! Kyi Kyi Mar’s was published by ကြည်ကြည်မာစာပေ (kyikyimar hcarpay) “Kyi Kyi Mar Literature” and Min Khite Soe San’s by ရွှေပဒေသာစာပေ (shway padaysar hcarpay) “Golden Literature”. Without Lucas’s insights I don’t think I ever would have worked out what was going on.

Pre-2012, the publisher entry in the front matter varies in its formatting but seems to regularly include 4 things:

- a person’s name—possibly the owner of the publishing house

- the name of the publishing house

- a registration number

- an address (not included above)

စာပေ (hcarpay) “Literature” is an extremely common suffix for publishers and it seems largely interchangeable with စာပေတိုက် (hcarpaytite) “Library”. I think, in fact, in this context, it would make more sense to translate the two words as “Publishing” and “Publishing House”, as I think it better captures the relationship between the words. In the two examples above, the registration numbers are off by one digit but otherwise the entries are fundamentally the same. I’m confident they are the same—which means that the same publisher produced two different translations of Philosopher’s stone at effectively the same time (about a month apart).

In the West, it would be inconceivable for a single publisher to issue competing translations of the same book in such rapid succession—and, wow, did that ever confuse me! However, when you consider the practice of renting publishing licenses, it starts to make more sense: ‘Sweet Music’ undoubtedly rented their license to Kyi Kyi Mar and Golden Literature and so are the official … publisher of record? printed on the inside for the military government. Who cares if they’re translations of the same book, if your only stake in the publication is a flat fee for lending out your registration? As far as the public is concerned they’re being published by two other entities: Kyi Kyi Mar Literature and Golden Literature.

Indeed, some of the later editions of Kyi Kyi Mar’s books, published by Seikku Cho Cho acknowledge their original publication by Kyi Kyi Mar Literature and by the time she published Goblet of Fire, it appears Kyi Kyi Mar Literature managed to get it’s own registration number.

Translators: Trying to sort out translators can be almost as difficult as publishers. Myanmar names are complicated; historically, there’s no tradition of family names and people can, and do, just change their names without any legal barriers. The language has a number of “honorifics”—sort of akin to English titles like Mr., Mrs., Dr., etc; however in Myanmar, they seem more obligatory—sort of as if, once you earn one of them, it becomes part of your name. Authors often use pen-names and a lot of both actual names and pen-names are quite common. Sometimes an author will distinguish themselves by appending a place name or organization name in brackets after their name. Between the variation in names, no widely used romanization standard, the newness of the internet and text-encoding issues, even just trying to find basic detail about an author can be incredibly difficult.

Kyi Kyi Mar, Min Khite Soe San and Kaung Myat Loon Taw—the three translators that appeared in Part 1—are thankfully pretty straight forward. But as I also alluded to in Part 1, I confirmed the existence of two more Philosopher’s Stone translations. One by “Nanda Thu”, Khin Maung Toe (Mongmit).

“Nanda Thu” I put in quotes because the translator’s actual name (I believe) is U Thaung Tin—Nanda Thu is a pen-name. “U” is one of those honorifics that I mentioned, so Thaung Tin would also be accurate. He also appears to have written under two other pen-names: Kyat Kale and Thet Long.

Khin Maung Toe (Mongmit)—I likely wouldn’t have given the parentheses a second thought if it wasn’t on the cover of the book, very clearly part of the translator’s name. That kind of prominence signifies importance. As it turns out, it’s a place name: Mongmit (aka Momeik) and so one of those qualifiers used to distinguish between multiple authors with the same name.

Since Part 1, I’ve also identified one more translator who appears, thankfully, to be another straight-forward character: Chit Oo Tin who has only translated Half-Blood Prince and Deathly Hallows. That said, initially Google translate was giving me “Oo Chit U Tin” as his name, so that did cause me quite a lot of confusion at first.

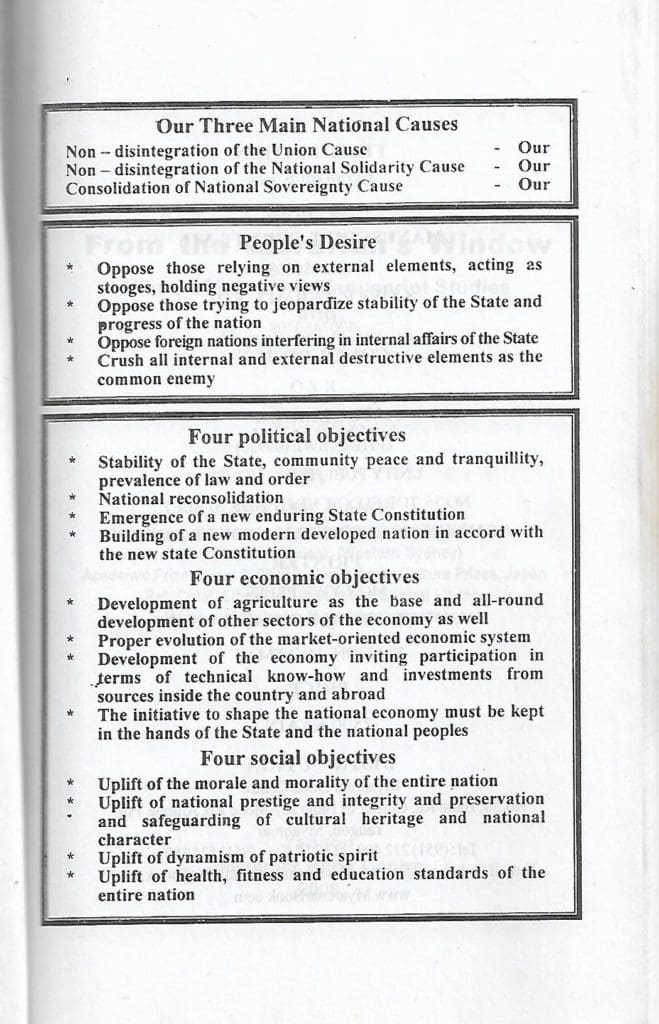

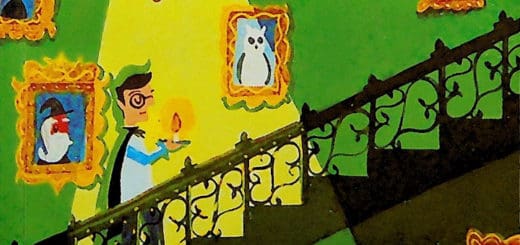

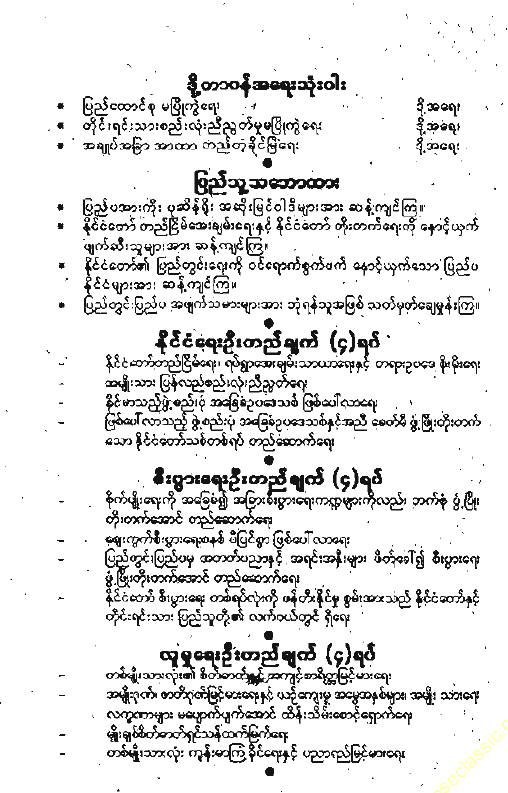

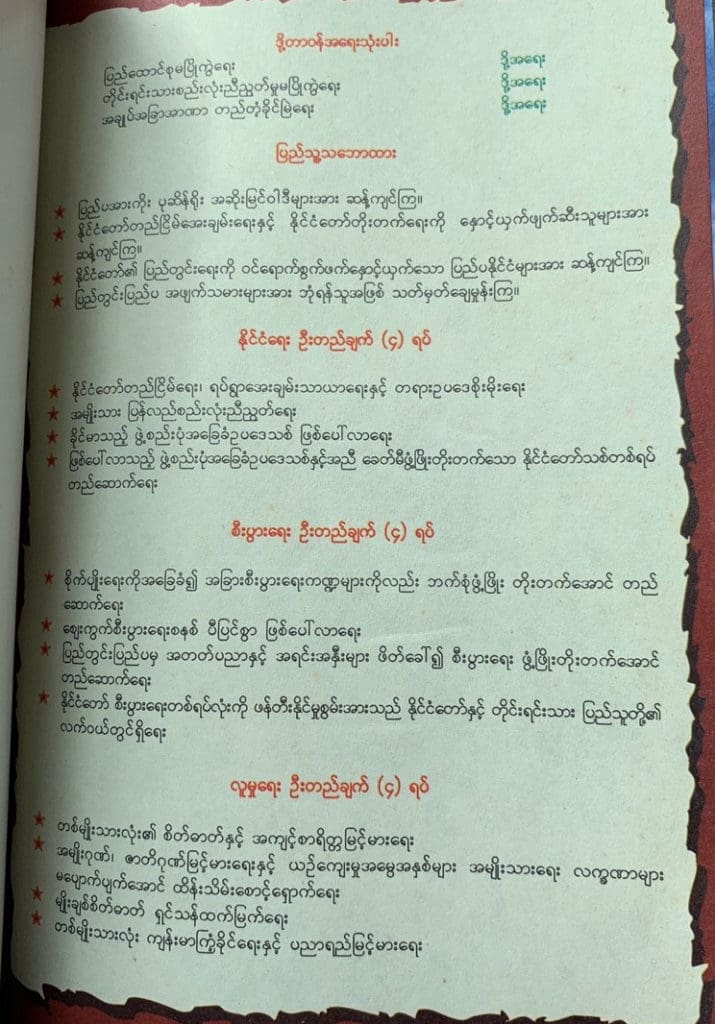

Mandated Clauses: When you open a book, there are a few pages that you expect to see—even across languages and cultures, globalization had made these pretty standard. These include the copyright page that provides most of the book’s ‘meta-data’, a title page, maybe a table of contents and probably a few blanks pages. Myanmar books pre-2012 (and post 1989) also have something that looks like these:

The crazy Google-translate examples I used up above come from these pages.

They are “Mandated Clauses”—a page of military-imposed statements of the state’s principles and goals. I did manage to surmise their purpose through Google’s tortured translations, but Lucas Stewart was able to provide me with a proper English version:

Ostensibly, this page of propaganda asserts that the content of the book is in line with military doctrine—or at least published with that intent. How true that may or may not be is up for debate—authoritarian regimes are not really known for consistency.

A really interesting question that unfortunately I’m in no position to answer as a non-speaker of the language is to what degree the content of the books were censored when they were originally published. All manuscripts had to go through the censorship board and it’s unlikely they would have made it through fully intact. Lucas tells me that at one point the censors would even scrub any reference to the colour ‘red’ because it was associated with the democratic, opposition party. The themes of Order of the Phoenix especially seem like exactly the kind of thing and authoritarian government would not want their public to read!

Theoretically, as I have both early pre and post 2012 texts, I could try and compare them, but I don’t think I’m up for a manual paragraph-by-paragraph comparison in that slippery Myanmar text. And it would take quite a lot of effort to get the texts into a sufficiently OCRable state to try and do a electronic comparison of the differences—for now it’s going to have to stay on my list of future projects.

An Authorized Translation?

In Part 1, I concluded that there are not any authorized translations in Myanmar. I haven’t changed that position—yet. It has softened a little based on two facts.

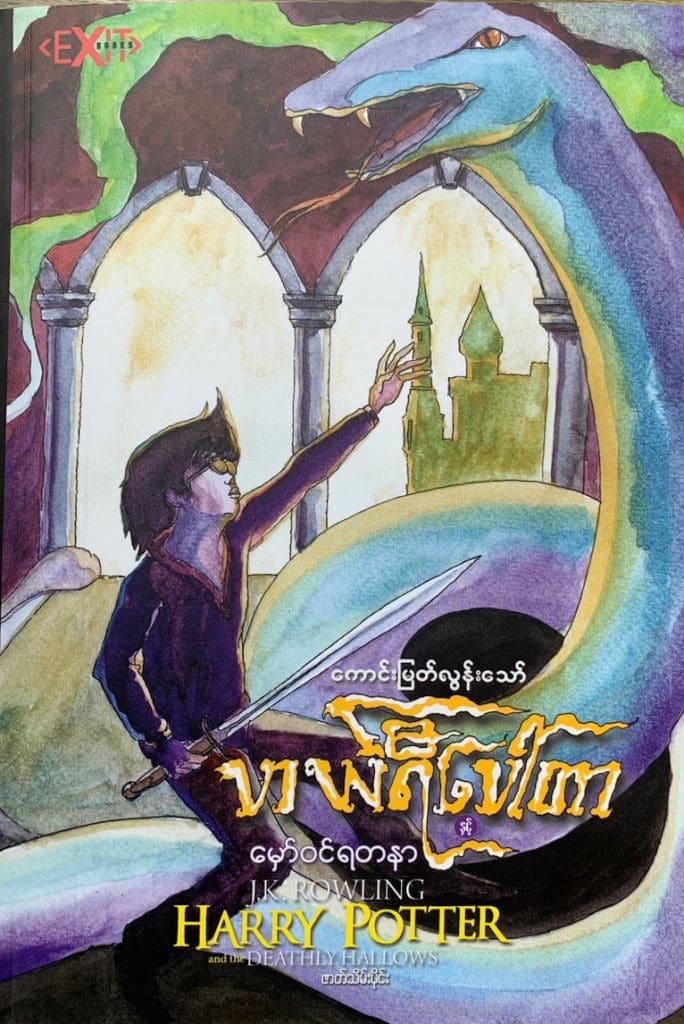

First Exit Books, the publisher of Khaung Myat Loon Taw’s translation (the most recent one with the psychedelic cover) is actually an imprint of NDSP Publishers. NDSP’s website—which has recently been replaced with a generic “parked” page—had a statement basically asserting that they adhered to respected international copyright. @mcallister_alaskagrown also contacted the publisher online through social media and a representative claimed that it was authorized.

Honestly, I didn’t put much stock in either statement—suppose you’re in the business of publishing illegal books, you’re not likely to just up and admit it publicly are you? Especially not to some a foreign stranger that doesn’t even speak your language. What good could come from that? Unless the claims of the publisher are backed up with other tangible evidence, then I don’t find them compelling.

However, then I talked to Lucas Stewart. He knows NDSP and its owner, San Mon Aung by reputation—he also owns the largest bookstore in Myanmar, the Yangon Book Plaza. Apparently San Mon Aung is “at the forefront of modernizing the publishing industry” in Myanmar by executing contracts with authors and paying proper royalties; he’s also well connected with the industry in the UK. Finally Lucas concluded that he’d be very surprised if the Exit edition is not an authorized translation.

Surprised, I raised my concerns about a lack of ISBN and consistent copyright page—criteria I am reasonably certain the Blair Partnership would/do insist on. While Lucas agreed that the Blair Partnership is probably quite strict on those technical details and that it would make the most sense for NDSP to adhere to them, he also pointed out again that Myanmar is still learning about international publishing standards and that foreign entities still have no legal recourse within Myanmar. NDSP could have agreed to The Blair Partnership’s stipulations in writing and for some reason simply decided to not implement them. The Blair Partnership could complain, but not actually do anything about it.

I have to admit this is a plausible sounding scenario. In fact, it very well could explain the only non-conforming, confirmed-authorized, copyright page: Persian. It’s published in another authoritarian regime, Iran, where again, the Blair Partnership would have no way to control how the book appeared. (Oh, wait—did some one say, “cover art“?)

Unfortunately, while that calls into question the admittedly flawed criteria I use in order to assess the status of any given translation, it still doesn’t provide a conclusive answer! So, short of word one way or the other from the Blair Partnership, it’s still an open question. (I have made an inquiry—maybe they’ll answer this time. Not going to hold my breath though.) Cautiously, I will leave my original assessment as it stands.

Update: Another pre-publication update—@mcallister_alaskagrown received some more information from a contact in Myanmar who apparently spoke with someone at NDSP. It seems that NDSP did in fact engage The Blair Partnership to obtain publication rights; however, they were refused due to the state of copyright law in Myanmar. While this is still effectively hearsay, it does help explain some of the contradictory facts. Moreover, it does leave hope that, as Myanmar brings its intellectual property legislation into line with international standards, one of these translations might get officially sanctioned.

Concluding Remarks

This investigation has really left me with the impression that we have only scratched the surface of unauthorized translations. Their underground nature make them difficult to research or even find. I used to think that they were relatively few and far between, often restricted to the first book or completed by impatient fans before the authorized translation was available. However, it is apparent that there are places in the world where the Harry Potter books are prolifically translated even within the same market, in competition with each other and even with an authorized version.

Here, I’ve identified 16 translations of the 7 books—and clearly they are not done. It seems quite likely that Kaung Myat Loon Taw will continue translating the books for Exit/NDSP. However, since stumbling onto these 16 Myanmar translations I’ve identified as many unauthorized Persian translations of Philosopher’s Stone. That’s not a typo—you read that right! 16 unauthorized Persian translations of just Philosopher’s Stone—that’s 17 including the authorized translation. I have found more than 80 different Persian translations of all 7 books.

It is going to be a long time—if ever—before “The List” can be considered as authoritative for unauthorized translations as it is for authorized ones!

The Catalogue

In order to provide complete details, I’m going to break address the translators, publishers and books separately. I am also going to include different reprints/editions of the books which is not my usual modus operandi of exclusively talking about translations. The primary reason for that is the unusual variation in publishers and the possibility that the texts are significantly different between printings due to censorship.

The Translators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Myanmar | Transliteration | English |

| ကြည်ကြည်မာ | kyikyimar | Kyi Kyi Mar |

| မင်းခိုက်စိုးစန် | mainnhkitehcoehcaan | Min Khite Soe San |

| ကောင်းမြတ်လွန်းဟော် | kaunggmyat lwann haw | Kaung Myat Loon Taw |

| ခင်မောင်တိုး (မိုးမိတ်) | hkainmaungtoe (moemate) | Khin Maung Toe (Mongmit) |

| နန္ဒသူ | nand suu | Nanda Thu |

| ချစ်ဦးတင် | hkyit u tain | Chit Oo Tin |

The Publishers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Myanmar | Transliteration | English | Notes |

| ကြည်ကြည်မာစာပေ ကြည်ကြည်မာစာပေတိုက် | kyikyimar hcarpay kyikyimar hcarpaytite | Kyi Kyi Mar Literature Kyi Kyi Mar Library | |

| ချိုတေးသံစာပေ ချိုတေးသံစာပေသိုလ် | hkyao tayysan hcarpay hkyao tayysan hcarpaytite | Choral Music Literature Choral Music Library | pub. of record used by Kyi Kyi Mar Literature/Library and Golden Literature |

| စိတ်ကူးချိုချိုစာပေ | hcatekuu hkyaohkyao hcarpay | Seikku Cho Cho Literature | |

| ရွှေပဒေသာ ရွှေပဒေသာစာပေ | shway padaysar shway padaysar hcarpay | Golden Golden Literature | |

| The Essence | imprint of Seikku Cho Cho | ||

| ဘဝတက္ကသိုလ်စာအုပ်တိုက် | bhaw takkasol hcarpaytite | University of Life Library | |

| Exit Books | division of NDSP Publishing House | ||

| NDSP Publishing House | |||

| စန္ဒဝင်းစာပေ | hcand wainn hcarpay | Sanda Win Literature | pub. of record used by Kyi Kyi Mar Literature/Library |

| ရွှေအိမ်မှူးစာပေ | shway aain mhauu hcarpay | Golden House Chief Literature | I hate this translation, but it was the best I could tease out! |

| သလ္လာဝတီစာပေ | sallarwate hcarpay | Theravada Literature | pub. of record used by Golden House Chief Literature |

| SKY TREASURE စာပေ | SKY TREASURE hcarpay | Sky Treasure Literature | |

Philosopher’s Stone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Translator | Date | Title / Transliteration / Translation | Publisher | |

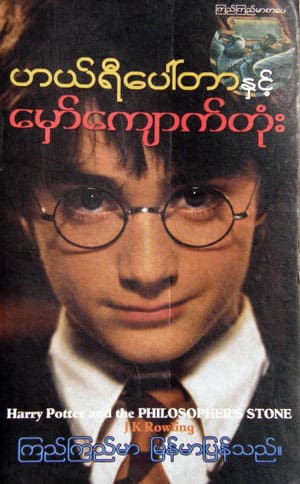

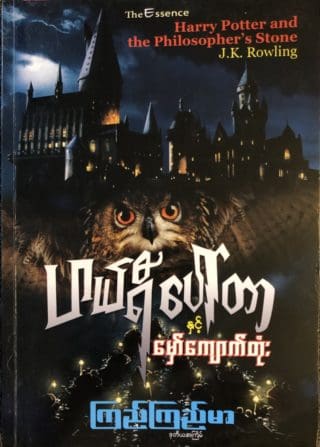

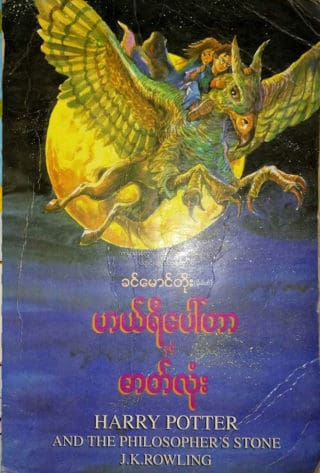

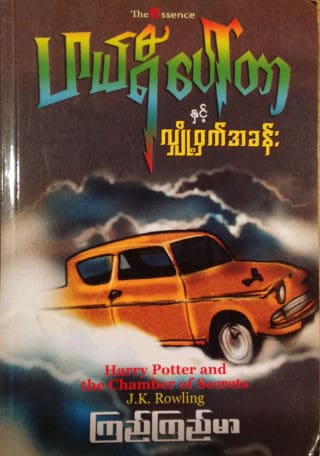

| Kyi Kyi Mar | 2002-09 | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်မှော်ကျောက်တုံး haalrepawtar nhang mhaaw kyawwattone Harry Potter and the magic stone2 | Kyi Kyi Mar Literature Choral Music Literature | |

| 2019-01 | The Essence (imprint) Seikku Cho Cho | |||

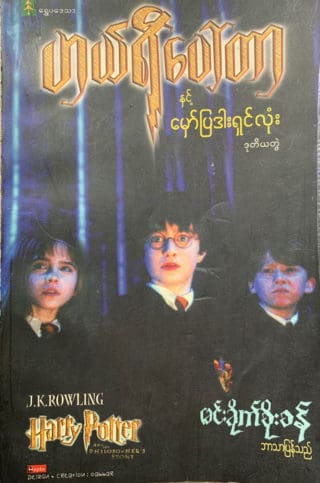

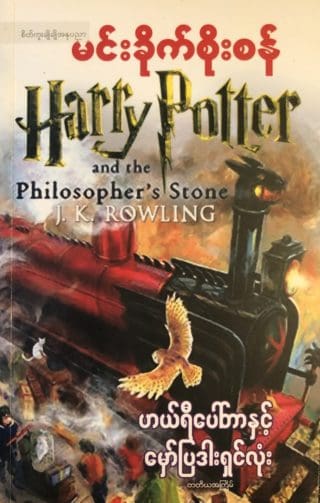

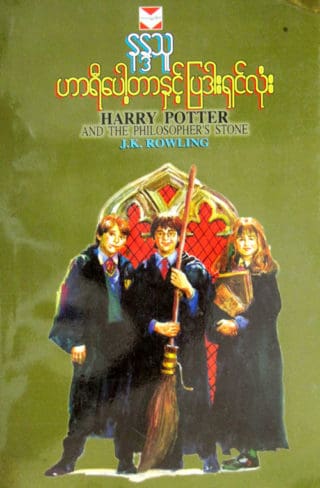

| Min Khite Soe San | 2002-10 (2 Vol) | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်မှော်ပြဒါးရှင်လုံး haalrepawtar nhang mhaaw pya darr shin lone | Golden Literature Choral Music Literature | |

| 2006 2016-04 (3rd printing) | Seikku Cho Cho | |||

| Khin Maun Toe | 2002 | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်ဓာတ်လုံး haalrepawtar nhang dharatlone | Unknown | |

| Nanda Thu | 2002 | ဟာရီပေါ့တာနှင့်ပြဒါးရှင်လုံး har re pot tar nhang pya darr shin lone | University of Life Library | |

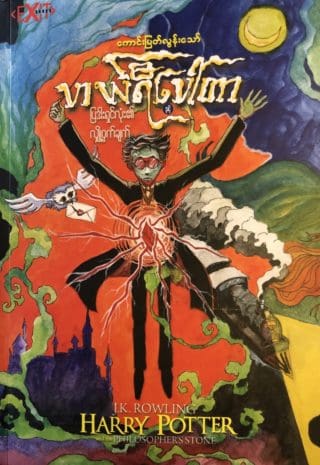

| Kaung Myat Loon Taw | 2019-08 | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်ပြဒါးရှင်၏ လျှို့ဝှက်ချက် haalrepawtar nhang pya darr shineat shhoetwhaathkyet | Exit Books | |

Chamber of Secrets | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Translator | Date | Title / Transliteration / Translation | Publisher | |

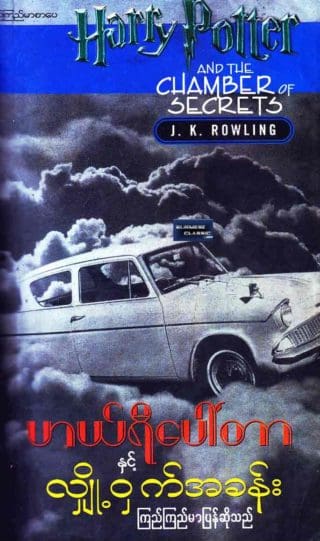

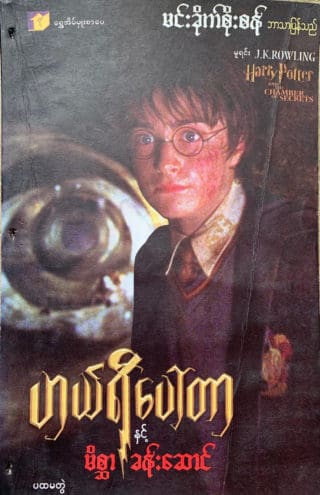

| Kyi Kyi Mar | 2003 | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်လျှို့ဝှက်အခန်း haalrepawtar nhang shhoetwhaataahkaann Harry Potter and the Secret Room |

Kyi Kyi Mar Literature Sanda Win Literature |

|

| 2018 | The Essence (imprint) Seikku Cho Cho |

|||

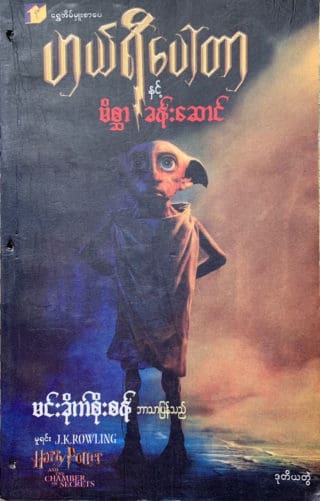

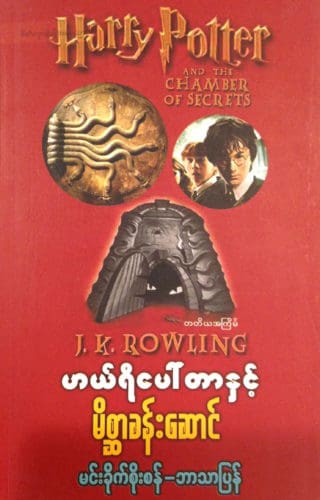

| Min Khite Soe San | 2004-02 (2 Vol) | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်မိစ္ဆာခန်းဆောင် haalrepawtar nhang mihcsar hkaannsaung Harry Potter and the False Room |

Golden House Chief Literature Theravada Literature |

|

| 2006 2015 (3rd printing) | Seikku Cho Cho | |||

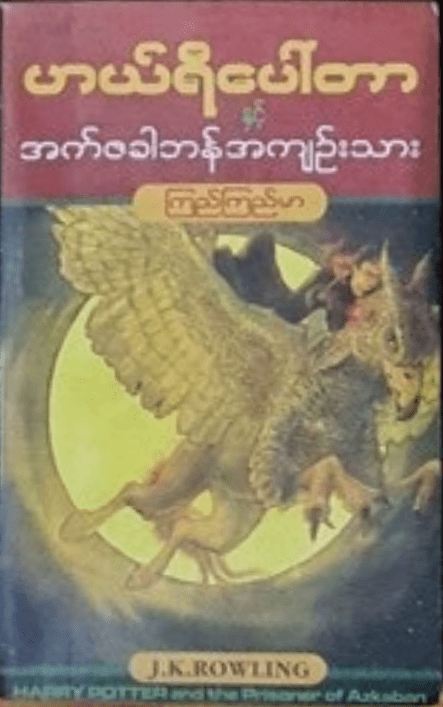

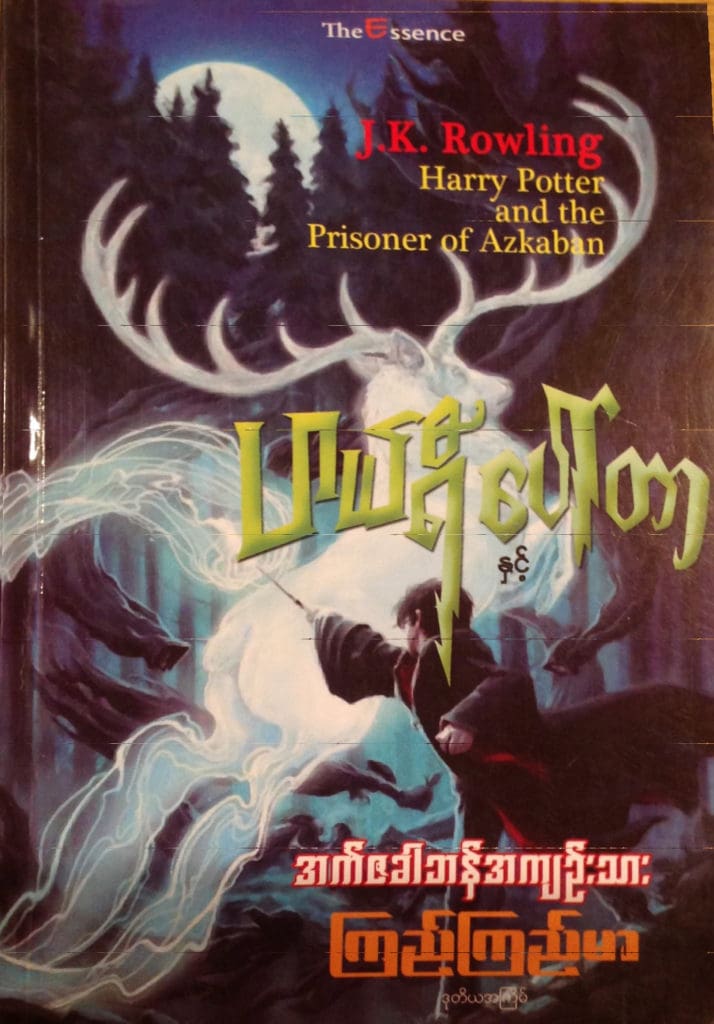

Prisoner of Azkaban | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| translator | date | title / transliteration / translation | publisher | |

| Kyi Kyi Mar | unknown | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်အက်ဇခါဘန်အကျဉ်းသား haalrepawtar nhang aaat j hkar bhaan aakyainsarr Harry Potter and the Azkaban Prisoner | unknown | |

| 2019-04 | The Essence Seikku Cho Cho | |||

| Min Khite Soe San | 2005 | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်ဝိညာဉ်နှုတ်အကျဉ်းသား haalrepawtar nhang winyarin nhuat aakyainsarr Harry Potter and the Spiritual Prisoner | Golden House Chief Literature | |

| 2014 | Seikku Cho Cho | |||

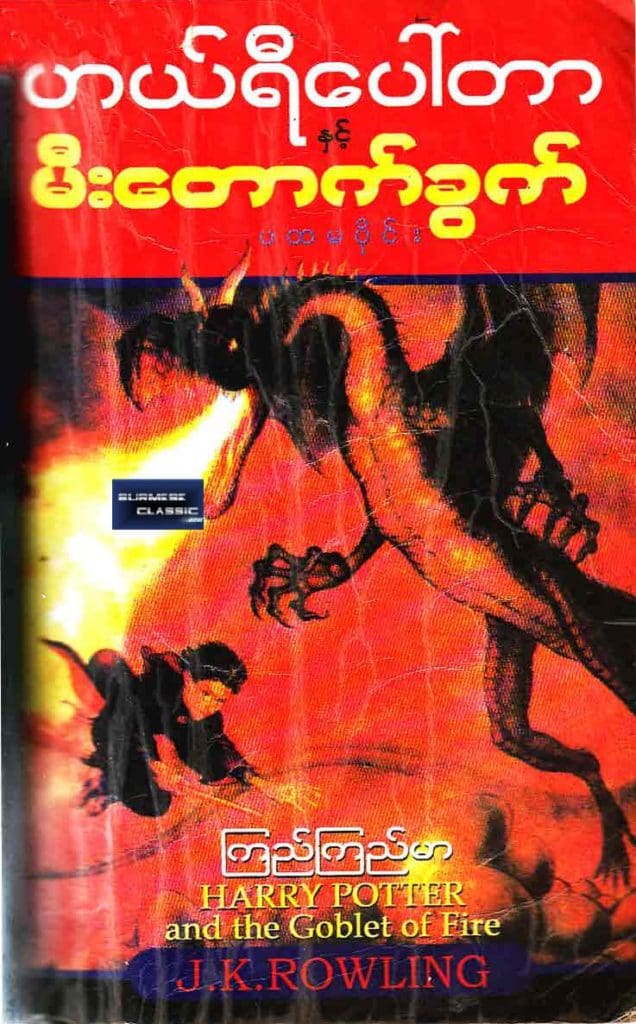

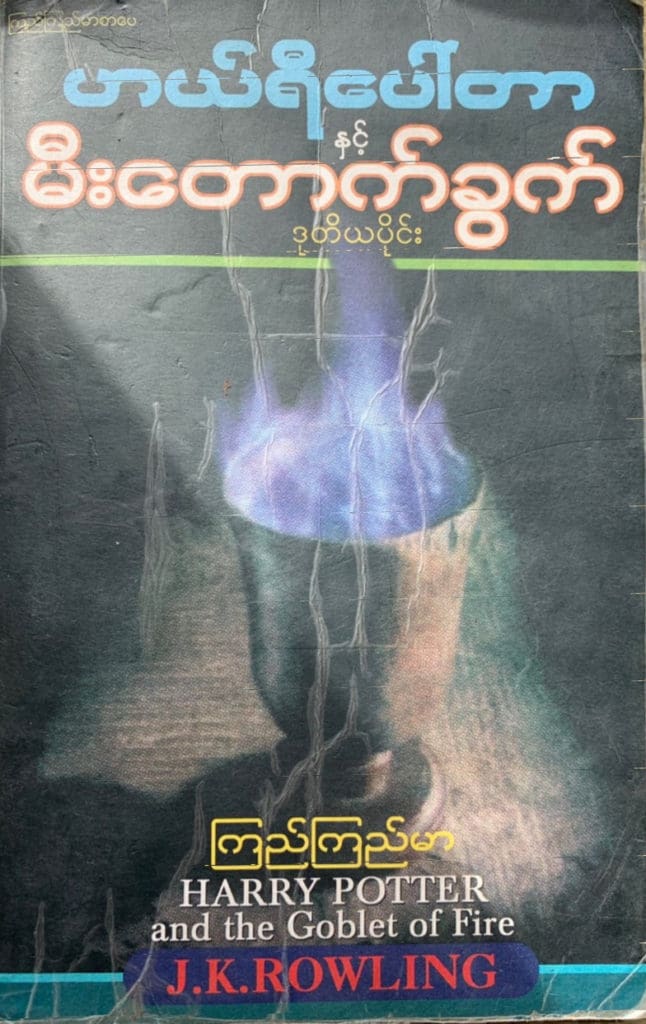

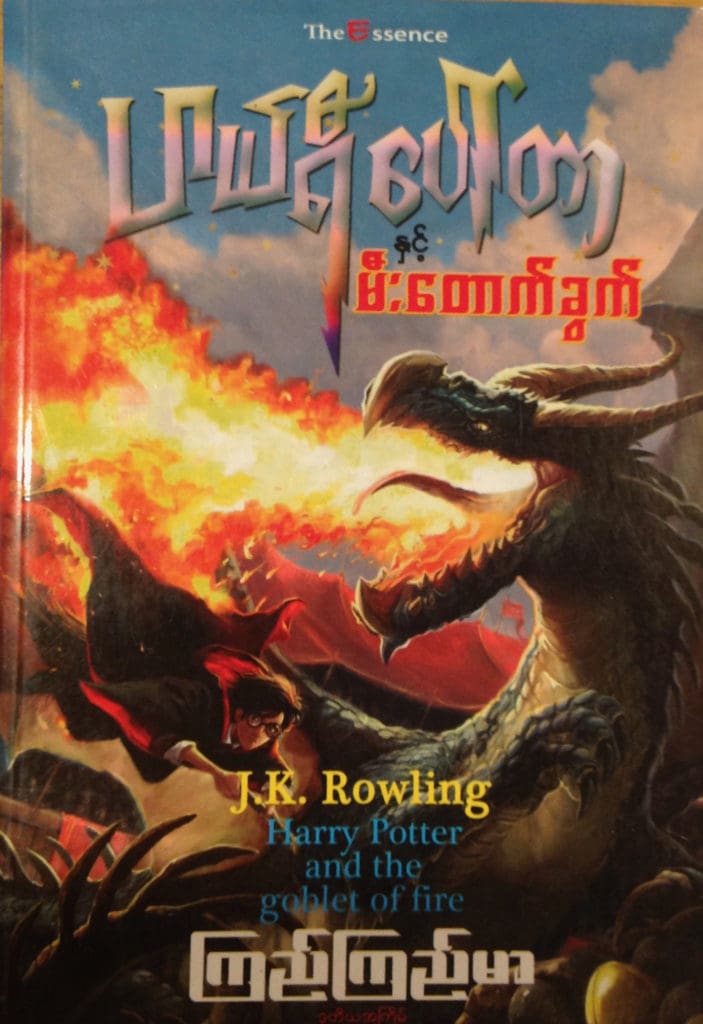

Goblet of Fire | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| translator | date | title / transliteration / translation | publisher | |

| Kyi Kyi Mar | 2005-03 (2 Vol) | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်မီးတောက်ခွက် haalrepawtar nhang meetout hkwat Harry Potter and the Cup of Flame | Kyi Kyi Mar Literature Kyi Kyi Mar Library | |

| 2019 | The Essence Seikku Cho Cho | |||

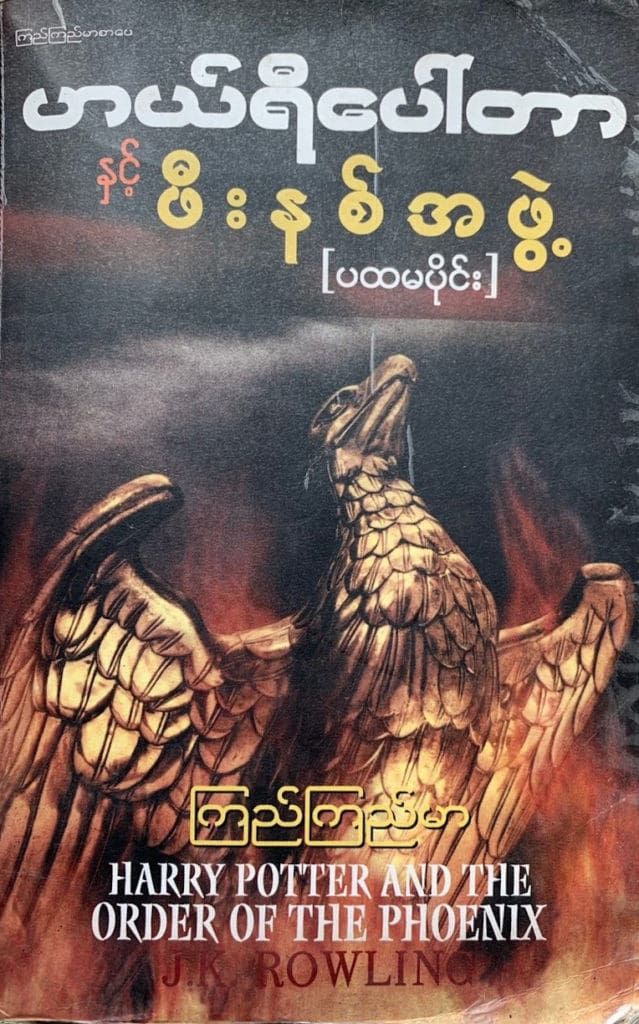

Order of the Phoenix | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| translator | date | title / transliteration / translation | publisher | |

| Kyi Kyi Mar | 2006 (2 Vol) | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်ဖီးနစ်အဖွဲ့ haalrepawtar nhang hpeenait aahpwal Harry Potter and the Phoenix Fellowship | Kyi Kyi Mar Literature Kyi Kyi Mar Library | |

| 2019 | The Essence Seikku Cho Cho | |||

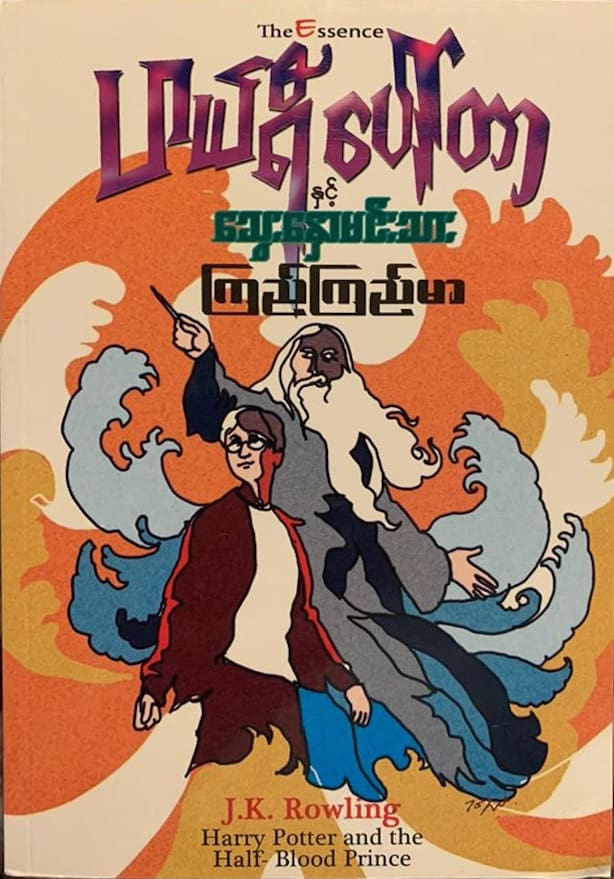

Half Blood Prince | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| translator | date | title / transliteration / translation | publisher | |

| Chit Oo Tin | 2006-07 | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်သွေးတစ်ဝက်မှော်ဝိဇ္ဇာ haalrepawtar nhang sway taitwaat mhaawwijjar Harry Potter and the Half-blood Magician | unknown | |

| Kyi Kyi Mar | 2006-09 | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်သွေးနှောမင်းသား haalrepawtar nhang sway nhaaw mainnsarr Harry Potter and the Mixed-blood Prince | Kyi Kyi Mar Literature Kyi Kyi Mar Library | |

| 2019-09 | The Essence Seikku Cho Cho | |||

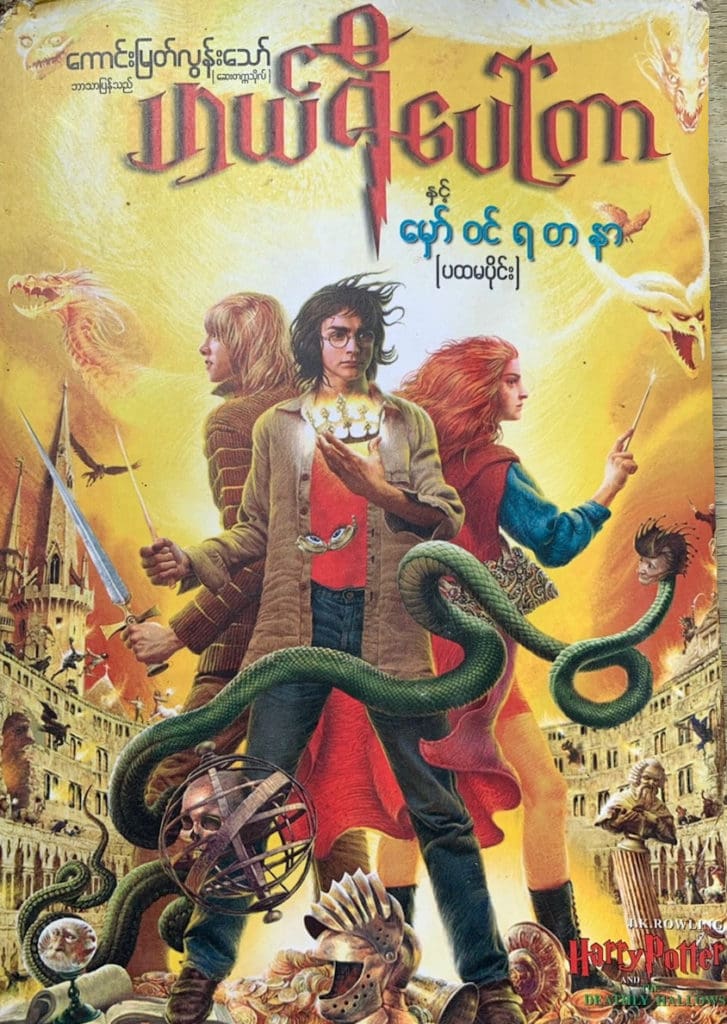

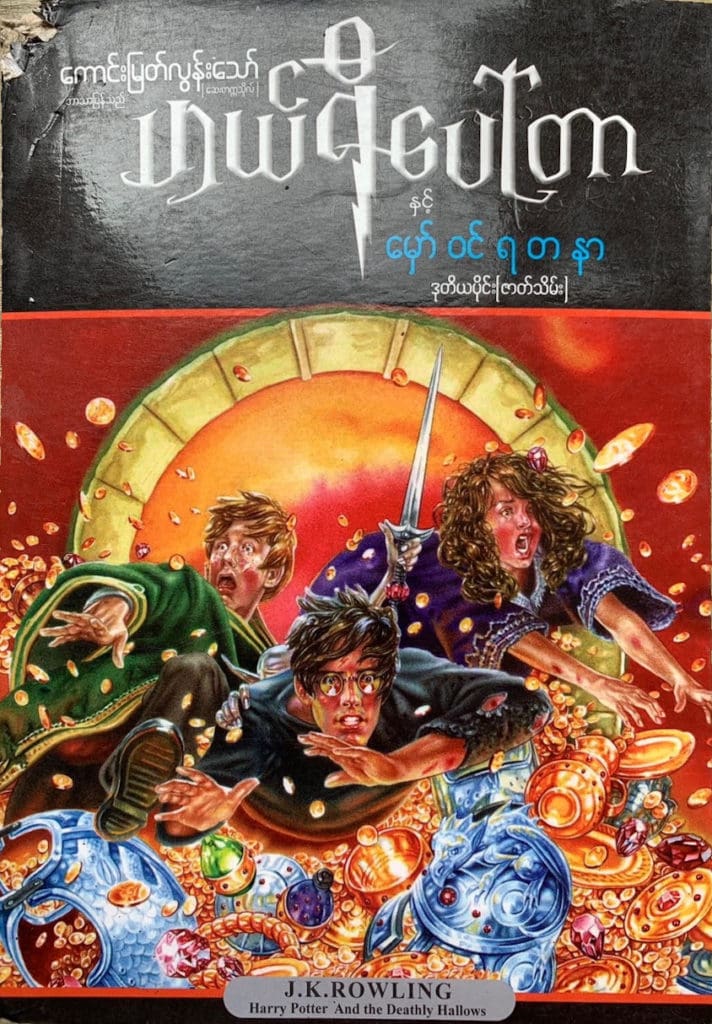

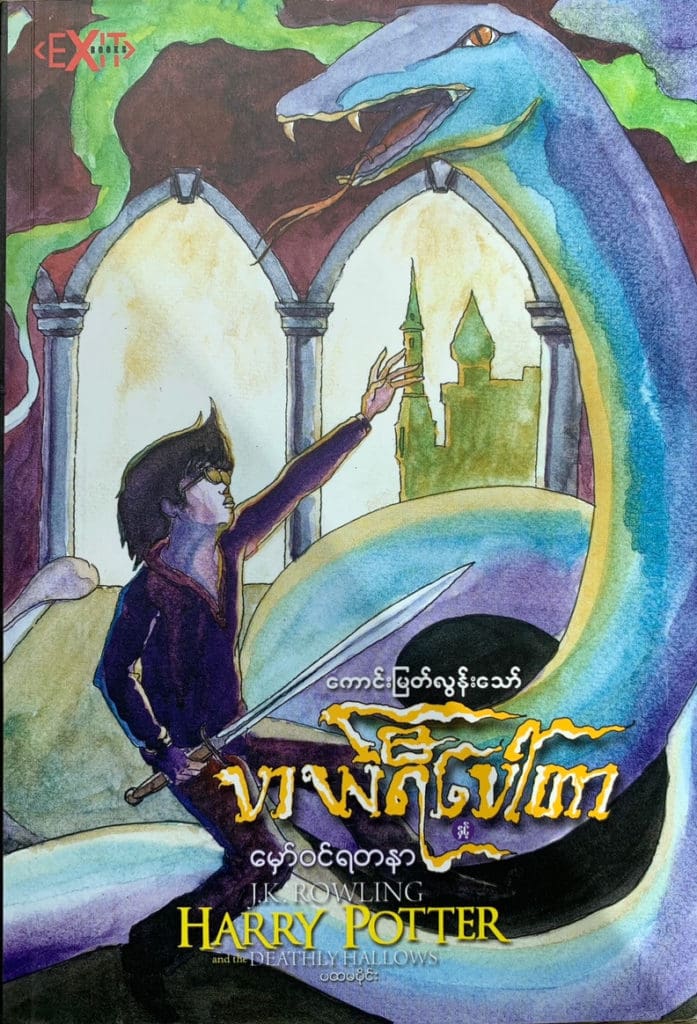

Deathly Hallows | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| translator | date | title / transliteration / translation | publisher | |

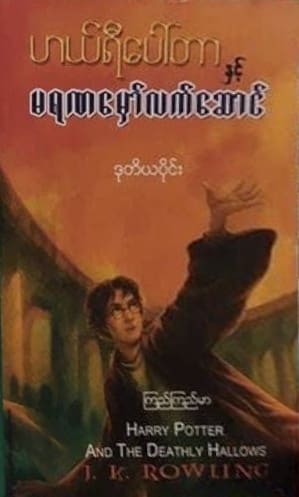

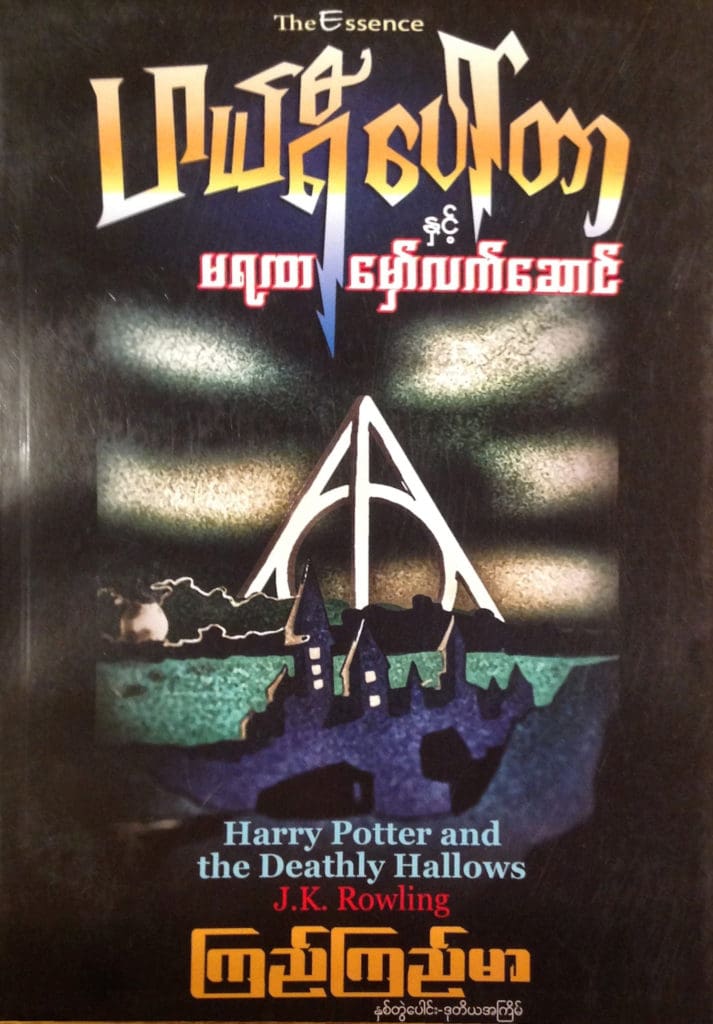

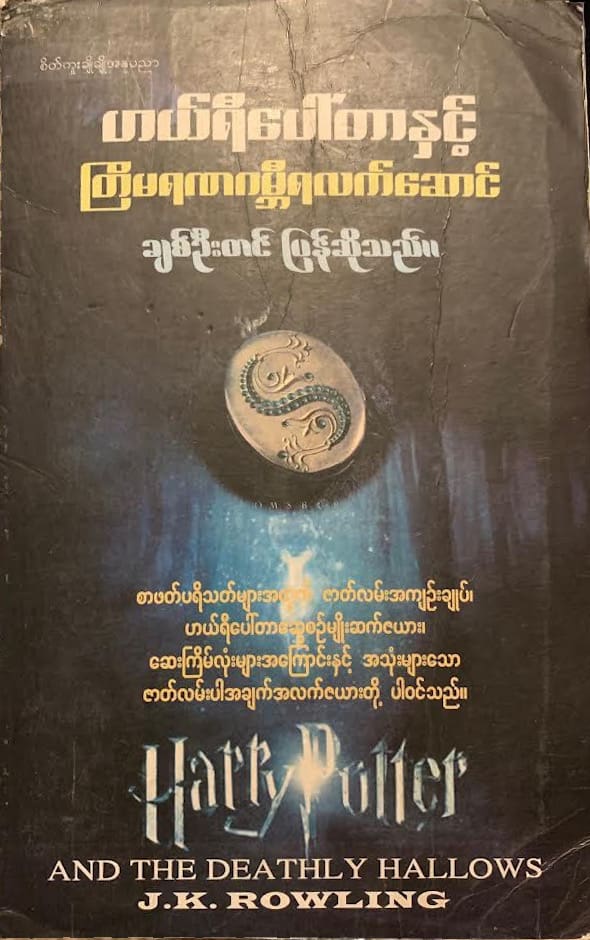

| Kaung Myat Loon Taw | 2007-10 (2 Vol) | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်မှော်ဝင်ရတနာ haalrepawtar nhang mhaawwain ratanar Harry Potter and the Magic Treasures | Sky Treasure | |

| 2019-08 (2 Vol) | Exit Books | |||

| Kyi Kyi Mar | 2008 | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်မရဏမှော်လက်ဆောင် haalrepawtar nhang maran mhaaw laatsaung Harry Potter and the Magic Gifts of Death | Kyi Kyi Mar Literature Kyi Kyi Mar Library | |

| unknown | unknown | |||

| 2018 | The Essence Seikku Cho Cho | |||

| Chit Oo Tin | 2009-05 | ဟယ်ရီပေါ်တာနှင့်တြိမရဏဂမ္ဘီရလက်ဆောင် haalrepawtar nhang tyai maran gambher laatsaung Harry Potter and the Three Mystical Gifts of Death | Seikku Cho Cho | |

Notes

- The pervasiveness for Facebook in Myanmar is actually a whole other massive issue as it played a role in exacerbating violence against the Rohingya people.

- This is the first translation that Google gave me in the spring of 2020; when I tried again in the fall it was hilariously “Harry Potter and the Ghostbusters”